Fans hold up a sign that says “St. Louis is Our Home” during a game between the St. Louis Rams and the San Francisco 49ers on Sunday, Nov. 1, 2015, at the Edward Jones Dome in St. Louis. Photo by Chris Lee, [email protected]

ST. LOUIS — It was 2014. The Super Bowl was a few days away. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell stepped to the mic at his annual Super Bowl-week news conference and told the world that he had no knowledge of any plans by St. Louis Rams owner Stan Kroenke to develop a stadium in Los Angeles. But that wasn’t true. Kroenke had long before briefed Goodell on his plan to buy the old Hollywood Park racetrack in Inglewood. Goodell promised confidentiality. Kroenke said he trusted him. “We’re going to try very hard to stay under the radar screen and nobody will know we bought it,” Kroenke told Goodell. “We’ll stay hidden, which is what we want, for as long as we can.” And the league was taking the same tack. Just a few hours before the news conference, one of Goodell’s lieutenants had sent an email to former Disney CEO Michael Eisner, who was working behind the scenes on a different effort to get the NFL back to Los Angeles. “I am trying to get a terrific LA opportunity to materialize,” wrote league Executive Vice President Eric Grubman. “And I want to do it under cover of darkness.”

Los Angeles Rams owner Stan Kroenke holds the Lombardi Trophy after the Rams defeated the Cincinnati Bengals in the NFL Super Bowl 56 football game Sunday, Feb. 13, 2022, in Inglewood, Calif. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

Now, almost six months after St. Louis lawyers secured a $790 million payment from the league to settle a suit over the Rams’ departure, hundreds of newly released court exhibits pull back the curtain on how it all happened. Together, the documents represent the most complete picture yet of how early Kroenke started planning his Los Angeles stadium, how closely the NFL worked with him to keep fans in the dark and just how deeply St. Louis lawyers got into the league’s inner sanctum. Among the highlights from the records, released by the NFL and the Rams in response to a motion filed with the court by the Post-Dispatch: • Kroenke and top Rams executive Kevin Demoff began talking about the Los Angeles stadium project in earnest in the summer of 2013, more than a year before they revealed their plans to the public. • In December of that year, Demoff sent Kroenke a secret memo laying out, in detail, strategies to get NFL permission to move the Rams, including a plan to highlight St. Louis’ “downward trend as a market.” • At least twice, the Rams and the NFL worked together on public statements obscuring Kroenke’s moves in LA, first after Kroenke bought land at Hollywood Park and then again when he leaked news that he was building a stadium there. • In March 2014, Kroenke and his partner in the Hollywood Park land deal discussed keeping the deal quiet “to maximize 2014 ticket sales by avoiding any unnecessary publicity about the possible departure of the Rams.”

People are also reading…

Documents obtained by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch describe the moments when Stanley Kroenke revealed plans to the NFL and minutes of the meeti…

• By the end, just two of the NFL team owners voted against the Rams’ move. Cincinnati Bengals owner Mike Brown was the only vote against any relocation to Los Angeles and was outspoken about it: “There’s nothing wrong with the markets where these teams play now,” he said at a meeting in 2015. • The league indeed contemplated, at one point, the Raiders moving to St. Louis, with restructured ownership and a brand makeover. But a decade ago, at least for a moment, St. Louis impressed the NFL.

‘He wants to be senator and we can be helpful’

In the summer of 2012, league executive Chris Hardart came to the city amid a dispute between the Rams and local leaders over upgrades to the Edward Jones Dome and found business community leaders “energized” and meetings productive. They talked about the league coming to help bridge the gap between the city and Kroenke. But in February 2013, arbitrators ruled in favor of Rams’ $700 million proposal to make the Edward Jones Dome a first-tier NFL facility, and on July 3, local leaders gave official notice they weren’t going to pony up. “We simply don’t have the money to do it,” said Jim Shrewsbury, head of the Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority.

The Edward Jones Dome, bottom, as seen looking northeast towards the site for a proposed new football stadium to be built in St. Louis along the Mississippi River north of downtown St. Louis as seen on Thursday, Jan. 15, 2015. Photo By David Carson, [email protected]

It was what Kroenke had been waiting to hear. On the same day the Rams got the letter from Shrewsbury, Kroenke got an email from someone with information on a couple hundred acres in Inglewood that would be good for a stadium. Within weeks, Kroenke was up before dawn driving around the property, Rams chief operating officer Kevin Demoff would later recall, according to court records. Demoff said he got a call from Kroenke at 5:15 a.m. Los Angeles time. “And if you’re getting a call from your boss at 7:15 and you know they’re on the West Coast,” Demoff said that day, “either it’s something really great or you’re about to fired, right?” “He goes, ‘I’m driving around Hollywood Park. This is an unbelievable site,’” Demoff continued. “We’re on the phone for two hours and he says, ‘I think this could work.’” “That,” Demoff said, “was the first time I ever thought this could become a reality.” Back in St. Louis, Dave Peacock, a former Anheuser-Busch executive, had begun talking with local business leaders and the mayor’s office about building a new stadium on the riverfront north of downtown. Peacock and Jeff Rainford, the mayor’s chief of staff, also met with Mark Kern, the St. Clair County board chair, about a stadium in the Metro East. Still, it wasn’t long before the prospect of a Rams move to Los Angeles began circulating among team owners. By October, a couple of them decided it was time to sit down. And so on Oct. 11, 2013, Kroenke got on a call with Goodell and the owners of the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Houston Texans and laid out the plan. With the city refusing to upgrade the Edward Jones Dome, the Rams could give notice to leave as soon as 2015, he said, according to notes taken by a league attorney. Kroenke, whose wife is Ann Walton, already had a line on the first chunk of land in Hollywood Park: It belonged to Walmart, and the company wanted to sell. Moreover, he had political connections in the area: “(U.S. Rep.) Maxine Waters is a very good friend,” he said. “And the Mayor (of Inglewood) is a hell of a guy. … He has already jumped on our train.” Bob McNair, then the owner of the Houston Texans, asked Kroenke if he could make St. Louis work. Kroenke expressed doubts. The city had lots of big companies when the team first moved to St. Louis in 1995, he said, but the base wasn’t there anymore. Sponsorship was down. “I’m not sure a new stadium does it for you,” he said. Goodell said he’d met with Gov. Jay Nixon and expressed concern that he might not take leaving lying down: Nixon had threatened to sue the league as state attorney general in the 1990s. But Kroenke didn’t seem concerned. “He’s not a bad guy,” Kroenke said. “He wants to be senator and we can be helpful to him.”

‘No plans, to my knowledge’

No one objected to Kroenke’s plans, and the men agreed to stay in touch. Meanwhile, back at Rams Park, work was beginning on the endgame. By early December, Demoff had gotten through the NFL’s relocation rules and wrote to Kroenke that they had a good shot at passing muster. But they had to get the messaging right. The league would require proof they really tried to work out the dome dispute. And St. Louis would likely offer a new stadium, Demoff said. The Rams had to prove that, even with a new stadium, St. Louis had “long-term challenges” and was an “unwise investment for both us and our league partners.” He suggested paying for a study to show it. “In the end, whatever engagement strategy we embark upon should be designed not to win over St. Louis but rather to win over New York,” he wrote. In January 2014, just weeks after Kroenke closed on the first piece of Hollywood Park land, the NFL heard from a reporter in Los Angeles looking to write a story right before the Super Bowl and asking for a comment from the league. Grubman, the league executive tasked with getting a team to LA, emailed Goodell asking whether they should reach out to Kroenke. “If we do, it is harder to play dunce,” Grubman wrote in an email on Jan. 28, 2014. “If we don’t we will not have his side.”

NFL Executive Vice President Eric Grubman responds to comments and questions during the NFL’s public hearing on potential relocation of the St. Louis Rams to Los Angeles on Tuesday, Oct. 27, 2015, at the Peabody Opera House in St. Louis. Photo by Chris Lee, [email protected]

They went with option 2. They also offered some pointers on deflection. Spokesman Greg Aiello emailed Demoff the next day and told him that Goodell and Jeff Pash, a league attorney, thought the Rams should stay out of the story and let Kroenke’s real estate company comment. The Rams took the advice. “As real estate developers, the Kroenke Organizations are involved in numerous real estate deals across the country and North America,” the statement from the Kroenke Group would later read. “We have yet to decide what we are going to do with the property.” Demoff took the same tack internally, telling employees the land buy was part of Kroenke’s real estate business. “Our focus will remain 100% on putting the best team on the field for St. Louis in 2014 and beyond,” he wrote in an email the day the story broke. Goodell said the same at his annual news conference before the Super Bowl: “Stan is a very large developer on a global basis. He has land throughout the country and throughout the world. “There are no plans, to my knowledge, of a stadium development.” Kroenke spent the following months securing the rest of the land for the stadium development. By March 2014, he had a term sheet from Stockbridge Capital Group. And in a draft of the agreement, Stockbridge explicitly said it understood Kroenke wanted to avoid any unnecessary publicity, partly to maximize ticket sales for the 2014 football season in St. Louis.

‘(Expletive) This (expletive) I’m Out’

Demoff, Kroenke and the NFL kept everything quiet for months. In fact, the very day that Gov. Nixon appointed Peacock, the former A-B executive, and attorney Bob Blitz to a two-man task force dedicated to keeping professional football here, Demoff applauded that start in an email to St. Louis hotelier Steve O’Loughlin. O’Loughlin was working to bring an aquarium to Union Station. He emailed Demoff, asking how he could respond to questions about the Rams leaving. Demoff called the task force a “positive first step.” Then, 60 days after the task force launched, the Los Angeles Times broke a bombshell: Kroenke had plans for an 80,000-seat stadium and a 6,000-seat performing arts theater at Hollywood Park. And once again, Kroenke’s men coordinated with the NFL on their message. In the hours before the story broke, Demoff emailed Aiello, the NFL spokesman, to tell him the Rams would again say the news was part of Kroenke’s real estate business. Aiello wrote back with a copy of the NFL’s statement noting that no team had applied for relocation and that the league was committed to having franchises be successful in their existing markets. Four days later, Peacock and Blitz unveiled their plan for a 64,000-seat, open-air stadium on St. Louis’ north riverfront. “This is about the future,” Peacock said. “We need to fight for what is rightfully ours.” But soon the St. Louis effort was mired in lawsuits, political wrangling and public outcry. Meanwhile, minutes of NFL owner’s meetings recorded growing certainty for Hollywood Park. “We own the land, the land is entitled, the design is complete, we are shovel-ready,” Kroenke said at a meeting in August. “We are ready to start digging in 100 days. With your help we will get this done.” And Demoff was writing emails to the NFL with links to negative stories about St. Louis: a Riverfront Times piece on the city’s murder rate, one Post-Dispatch article on economic stagnation and another on the city’s downgraded credit rating.

Los Angeles Rams COO Kevin Demoff watches during warm ups before an NFL football game against the Minnesota Vikings Thursday, Sept. 27, 2018, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Mark J. Terrill)

He and his deputies also traded emails blasting the task force’s announcement of National Rental Car, a brand of Clayton-based Enterprise Holdings, as the naming sponsor of the proposed riverfront stadium — the company, they said, hadn’t put much money into the Rams, thus far. “They have such a history of apathy and non-support then puff their chests out for support of a theoretical building that will likely not end up costing them anything,” wrote Jake Bye, who led ticket sales operations. Demoff replied with a link to what he called his formal response to the task force: a YouTube video called “(Expletive) This (expletive) I’m Out.”

‘I am not just an exec. I am a fan.’

Over the next months, NFL owners would go back and forth on the deal and whether the San Diego Chargers or Oakland Raiders should join them. At one meeting in November, there was even talk of bringing the Raiders to St. Louis with restructured ownership, a brand makeover and a commitment to a “special diversity initiative,” according to Goodell’s copy of the agenda. It went nowhere. Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones piped up for Kroenke at every opportunity. But others were gun-shy. In one meeting in December, the Arizona Cardinals’ Michael Bidwill wondered how the owners could live with ditching St. Louis if it was a viable option. “It sends a message to our fans that we are all about the Benjamins,” he said, according to notes on the meeting shared between Indianapolis Colts owners. A few were opposed to the relocation altogether. “I think all these teams are successful being where they are,” said Brown, the Bengals owner, according to the notes. “Shouldn’t we be supportive of the markets that have supported us for all these years?”

FILE – In this July 23, 2019, file photo, Mike Brown, owner of the Cincinnati Bengals NFL football team, speaks while being interviewed at Paul Brown Stadium during the team’s media luncheon in Cincinnati. The 2020 NFL Draft is April 23-25. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

On Dec. 6, the Rams officially filed for relocation, and true to Demoff’s plan, drawn up three years earlier, they said St. Louis was a city on the decline. On Jan. 12 in Houston, Kroenke and the owners of the Raiders and the Chargers all made their final presentations. The first vote that day was on the terms of relocation, which required teams to pay $64.5 million plus 25% of local revenue each year for 10 years. That passed easily, with only Cincinnati voting no. And after a few rounds of voting, Kroenke had approval to do what he’d been working toward for years. The Rams began planning games at the Los Angeles Coliseum while construction began on SoFi Stadium. U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill said she would draft a bill to claw back public dollars from sports teams that prematurely leave their hometowns. Stunned St. Louisans raged at Kroenke, the NFL and false hopes dashed in a single afternoon.

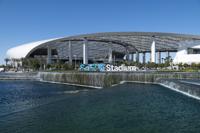

General view of SoFi Stadium, the home of the Los Angeles Rams before an NFL football game between the Los Angeles Rams and the Chicago Bears Sunday, Sept. 12, 2021, in Inglewood, Calif. (AP Photo/Kyusung Gong)

Kroenke, for his part, probably expected it. In an email dated May 18, 2016, titled “Thoughts,” he wrote that he had known he would be turned into a villain in his home state. But the league offices were not without sympathy for St. Louis. Months later, Grubman, while responding to an inquiry from a local reporter, asked how St. Louis was doing. “I know it is still raw where you are, and probably always will be,” he wrote. He said he’d recently been in Baltimore and had run into a guy who brought up the Colts leaving the city in 1984. “I am not just an exec,” Grubman wrote. “I am a fan.” But when the reporter replied that things were indeed raw in St. Louis, made worse by how the city was treated during the relocation process, Grubman took exception. “I understand the emotion,” he said, “but blaming the league is just wrong.”

Fans hold up a sign that says “St. Louis is Our Home” during a game between the St. Louis Rams and the San Francisco 49ers on Sunday, Nov. 1, 2015, at the Edward Jones Dome in St. Louis. Photo by Chris Lee, [email protected]

ST. LOUIS — It was 2014. The Super Bowl was a few days away. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell stepped to the mic at his annual Super Bowl-week news conference and told the world that he had no knowledge of any plans by St. Louis Rams owner Stan Kroenke to develop a stadium in Los Angeles.

But that wasn’t true. Kroenke had long before briefed Goodell on his plan to buy the old Hollywood Park racetrack in Inglewood. Goodell promised confidentiality. Kroenke said he trusted him.

“We’re going to try very hard to stay under the radar screen and nobody will know we bought it,” Kroenke told Goodell. “We’ll stay hidden, which is what we want, for as long as we can.”

And the league was taking the same tack. Just a few hours before the news conference, one of Goodell’s lieutenants had sent an email to former Disney CEO Michael Eisner, who was working behind the scenes on a different effort to get the NFL back to Los Angeles.

“I am trying to get a terrific LA opportunity to materialize,” wrote league Executive Vice President Eric Grubman. “And I want to do it under cover of darkness.”

Los Angeles Rams owner Stan Kroenke holds the Lombardi Trophy after the Rams defeated the Cincinnati Bengals in the NFL Super Bowl 56 football game Sunday, Feb. 13, 2022, in Inglewood, Calif. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

Now, almost six months after St. Louis lawyers secured a $790 million payment from the league to settle a suit over the Rams’ departure, hundreds of newly released court exhibits pull back the curtain on how it all happened. Together, the documents represent the most complete picture yet of how early Kroenke started planning his Los Angeles stadium, how closely the NFL worked with him to keep fans in the dark and just how deeply St. Louis lawyers got into the league’s inner sanctum.

Among the highlights from the records, released by the NFL and the Rams in response to a motion filed with the court by the Post-Dispatch:

• Kroenke and top Rams executive Kevin Demoff began talking about the Los Angeles stadium project in earnest in the summer of 2013, more than a year before they revealed their plans to the public.

• In December of that year, Demoff sent Kroenke a secret memo laying out, in detail, strategies to get NFL permission to move the Rams, including a plan to highlight St. Louis’ “downward trend as a market.”

• At least twice, the Rams and the NFL worked together on public statements obscuring Kroenke’s moves in LA, first after Kroenke bought land at Hollywood Park and then again when he leaked news that he was building a stadium there.

• In March 2014, Kroenke and his partner in the Hollywood Park land deal discussed keeping the deal quiet “to maximize 2014 ticket sales by avoiding any unnecessary publicity about the possible departure of the Rams.”

Documents obtained by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch describe the moments when Stanley Kroenke revealed plans to the NFL and minutes of the meeti…

• By the end, just two of the NFL team owners voted against the Rams’ move. Cincinnati Bengals owner Mike Brown was the only vote against any relocation to Los Angeles and was outspoken about it: “There’s nothing wrong with the markets where these teams play now,” he said at a meeting in 2015.

• The league indeed contemplated, at one point, the Raiders moving to St. Louis, with restructured ownership and a brand makeover.

But a decade ago, at least for a moment, St. Louis impressed the NFL.

‘He wants to be senator and we can be helpful’

In the summer of 2012, league executive Chris Hardart came to the city amid a dispute between the Rams and local leaders over upgrades to the Edward Jones Dome and found business community leaders “energized” and meetings productive. They talked about the league coming to help bridge the gap between the city and Kroenke.

But in February 2013, arbitrators ruled in favor of Rams’ $700 million proposal to make the Edward Jones Dome a first-tier NFL facility, and on July 3, local leaders gave official notice they weren’t going to pony up.

“We simply don’t have the money to do it,” said Jim Shrewsbury, head of the Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority.

The Edward Jones Dome, bottom, as seen looking northeast towards the site for a proposed new football stadium to be built in St. Louis along the Mississippi River north of downtown St. Louis as seen on Thursday, Jan. 15, 2015. Photo By David Carson, [email protected]

It was what Kroenke had been waiting to hear. On the same day the Rams got the letter from Shrewsbury, Kroenke got an email from someone with information on a couple hundred acres in Inglewood that would be good for a stadium.

Within weeks, Kroenke was up before dawn driving around the property, Rams chief operating officer Kevin Demoff would later recall, according to court records. Demoff said he got a call from Kroenke at 5:15 a.m. Los Angeles time.

“And if you’re getting a call from your boss at 7:15 and you know they’re on the West Coast,” Demoff said that day, “either it’s something really great or you’re about to fired, right?”

“He goes, ‘I’m driving around Hollywood Park. This is an unbelievable site,’” Demoff continued. “We’re on the phone for two hours and he says, ‘I think this could work.’”

“That,” Demoff said, “was the first time I ever thought this could become a reality.”

Back in St. Louis, Dave Peacock, a former Anheuser-Busch executive, had begun talking with local business leaders and the mayor’s office about building a new stadium on the riverfront north of downtown. Peacock and Jeff Rainford, the mayor’s chief of staff, also met with Mark Kern, the St. Clair County board chair, about a stadium in the Metro East.

Still, it wasn’t long before the prospect of a Rams move to Los Angeles began circulating among team owners. By October, a couple of them decided it was time to sit down. And so on Oct. 11, 2013, Kroenke got on a call with Goodell and the owners of the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Houston Texans and laid out the plan.

With the city refusing to upgrade the Edward Jones Dome, the Rams could give notice to leave as soon as 2015, he said, according to notes taken by a league attorney. Kroenke, whose wife is Ann Walton, already had a line on the first chunk of land in Hollywood Park: It belonged to Walmart, and the company wanted to sell. Moreover, he had political connections in the area:

“(U.S. Rep.) Maxine Waters is a very good friend,” he said. “And the Mayor (of Inglewood) is a hell of a guy. … He has already jumped on our train.”

Bob McNair, then the owner of the Houston Texans, asked Kroenke if he could make St. Louis work. Kroenke expressed doubts. The city had lots of big companies when the team first moved to St. Louis in 1995, he said, but the base wasn’t there anymore. Sponsorship was down.

“I’m not sure a new stadium does it for you,” he said.

Goodell said he’d met with Gov. Jay Nixon and expressed concern that he might not take leaving lying down: Nixon had threatened to sue the league as state attorney general in the 1990s.

But Kroenke didn’t seem concerned.

“He’s not a bad guy,” Kroenke said. “He wants to be senator and we can be helpful to him.”

‘No plans, to my knowledge’

No one objected to Kroenke’s plans, and the men agreed to stay in touch. Meanwhile, back at Rams Park, work was beginning on the endgame. By early December, Demoff had gotten through the NFL’s relocation rules and wrote to Kroenke that they had a good shot at passing muster. But they had to get the messaging right.

The league would require proof they really tried to work out the dome dispute. And St. Louis would likely offer a new stadium, Demoff said. The Rams had to prove that, even with a new stadium, St. Louis had “long-term challenges” and was an “unwise investment for both us and our league partners.” He suggested paying for a study to show it.

“In the end, whatever engagement strategy we embark upon should be designed not to win over St. Louis but rather to win over New York,” he wrote.

In January 2014, just weeks after Kroenke closed on the first piece of Hollywood Park land, the NFL heard from a reporter in Los Angeles looking to write a story right before the Super Bowl and asking for a comment from the league.

Grubman, the league executive tasked with getting a team to LA, emailed Goodell asking whether they should reach out to Kroenke.

“If we do, it is harder to play dunce,” Grubman wrote in an email on Jan. 28, 2014. “If we don’t we will not have his side.”

NFL Executive Vice President Eric Grubman responds to comments and questions during the NFL’s public hearing on potential relocation of the St. Louis Rams to Los Angeles on Tuesday, Oct. 27, 2015, at the Peabody Opera House in St. Louis. Photo by Chris Lee, [email protected]

They also offered some pointers on deflection. Spokesman Greg Aiello emailed Demoff the next day and told him that Goodell and Jeff Pash, a league attorney, thought the Rams should stay out of the story and let Kroenke’s real estate company comment.

The Rams took the advice.

“As real estate developers, the Kroenke Organizations are involved in numerous real estate deals across the country and North America,” the statement from the Kroenke Group would later read. “We have yet to decide what we are going to do with the property.”

Demoff took the same tack internally, telling employees the land buy was part of Kroenke’s real estate business.

“Our focus will remain 100% on putting the best team on the field for St. Louis in 2014 and beyond,” he wrote in an email the day the story broke.

Goodell said the same at his annual news conference before the Super Bowl: “Stan is a very large developer on a global basis. He has land throughout the country and throughout the world.

“There are no plans, to my knowledge, of a stadium development.”

Kroenke spent the following months securing the rest of the land for the stadium development. By March 2014, he had a term sheet from Stockbridge Capital Group. And in a draft of the agreement, Stockbridge explicitly said it understood Kroenke wanted to avoid any unnecessary publicity, partly to maximize ticket sales for the 2014 football season in St. Louis.

‘(Expletive) This (expletive) I’m Out’

Demoff, Kroenke and the NFL kept everything quiet for months.

In fact, the very day that Gov. Nixon appointed Peacock, the former A-B executive, and attorney Bob Blitz to a two-man task force dedicated to keeping professional football here, Demoff applauded that start in an email to St. Louis hotelier Steve O’Loughlin.

O’Loughlin was working to bring an aquarium to Union Station. He emailed Demoff, asking how he could respond to questions about the Rams leaving. Demoff called the task force a “positive first step.”

Then, 60 days after the task force launched, the Los Angeles Times broke a bombshell: Kroenke had plans for an 80,000-seat stadium and a 6,000-seat performing arts theater at Hollywood Park.

And once again, Kroenke’s men coordinated with the NFL on their message. In the hours before the story broke, Demoff emailed Aiello, the NFL spokesman, to tell him the Rams would again say the news was part of Kroenke’s real estate business. Aiello wrote back with a copy of the NFL’s statement noting that no team had applied for relocation and that the league was committed to having franchises be successful in their existing markets.

Four days later, Peacock and Blitz unveiled their plan for a 64,000-seat, open-air stadium on St. Louis’ north riverfront.

“This is about the future,” Peacock said. “We need to fight for what is rightfully ours.”

But soon the St. Louis effort was mired in lawsuits, political wrangling and public outcry. Meanwhile, minutes of NFL owner’s meetings recorded growing certainty for Hollywood Park.

“We own the land, the land is entitled, the design is complete, we are shovel-ready,” Kroenke said at a meeting in August. “We are ready to start digging in 100 days. With your help we will get this done.”

And Demoff was writing emails to the NFL with links to negative stories about St. Louis: a Riverfront Times piece on the city’s murder rate, one Post-Dispatch article on economic stagnation and another on the city’s downgraded credit rating.

Los Angeles Rams COO Kevin Demoff watches during warm ups before an NFL football game against the Minnesota Vikings Thursday, Sept. 27, 2018, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Mark J. Terrill)

He and his deputies also traded emails blasting the task force’s announcement of National Rental Car, a brand of Clayton-based Enterprise Holdings, as the naming sponsor of the proposed riverfront stadium — the company, they said, hadn’t put much money into the Rams, thus far.

“They have such a history of apathy and non-support then puff their chests out for support of a theoretical building that will likely not end up costing them anything,” wrote Jake Bye, who led ticket sales operations.

Demoff replied with a link to what he called his formal response to the task force: a YouTube video called “(Expletive) This (expletive) I’m Out.”

‘I am not just an exec. I am a fan.’

Over the next months, NFL owners would go back and forth on the deal and whether the San Diego Chargers or Oakland Raiders should join them. At one meeting in November, there was even talk of bringing the Raiders to St. Louis with restructured ownership, a brand makeover and a commitment to a “special diversity initiative,” according to Goodell’s copy of the agenda. It went nowhere.

Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones piped up for Kroenke at every opportunity. But others were gun-shy.

In one meeting in December, the Arizona Cardinals’ Michael Bidwill wondered how the owners could live with ditching St. Louis if it was a viable option.

“It sends a message to our fans that we are all about the Benjamins,” he said, according to notes on the meeting shared between Indianapolis Colts owners.

A few were opposed to the relocation altogether.

“I think all these teams are successful being where they are,” said Brown, the Bengals owner, according to the notes. “Shouldn’t we be supportive of the markets that have supported us for all these years?”

FILE – In this July 23, 2019, file photo, Mike Brown, owner of the Cincinnati Bengals NFL football team, speaks while being interviewed at Paul Brown Stadium during the team’s media luncheon in Cincinnati. The 2020 NFL Draft is April 23-25. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

On Dec. 6, the Rams officially filed for relocation, and true to Demoff’s plan, drawn up three years earlier, they said St. Louis was a city on the decline.

On Jan. 12 in Houston, Kroenke and the owners of the Raiders and the Chargers all made their final presentations.

The first vote that day was on the terms of relocation, which required teams to pay $64.5 million plus 25% of local revenue each year for 10 years. That passed easily, with only Cincinnati voting no. And after a few rounds of voting, Kroenke had approval to do what he’d been working toward for years.

The Rams began planning games at the Los Angeles Coliseum while construction began on SoFi Stadium. U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill said she would draft a bill to claw back public dollars from sports teams that prematurely leave their hometowns. Stunned St. Louisans raged at Kroenke, the NFL and false hopes dashed in a single afternoon.

General view of SoFi Stadium, the home of the Los Angeles Rams before an NFL football game between the Los Angeles Rams and the Chicago Bears Sunday, Sept. 12, 2021, in Inglewood, Calif. (AP Photo/Kyusung Gong)

Kroenke, for his part, probably expected it. In an email to himself dated May 18, 2016, he wrote that he had known he would be turned into a villain in his home state.

But the league offices were not without sympathy for St. Louis.

Months later, Grubman, while responding to an inquiry from a local reporter, asked how St. Louis was doing.

“I know it is still raw where you are, and probably always will be,” he wrote. He said he’d recently been in Baltimore and had run into a guy who brought up the Colts leaving the city in 1984.

“I am not just an exec,” Grubman wrote. “I am a fan.”

But when the reporter replied that things were indeed raw in St. Louis, made worse by how the city was treated during the relocation process, Grubman took exception.

“I understand the emotion,” he said, “but blaming the league is just wrong.”